In Greek mythology, Erebus is the primeval god of darkness, son of Chaos. It’s also the region of the underworld, where souls pass through after dying. The word is so evocative of gloom and shadows that naming one of the most dangerous types of Bitcoin attacks after it seems only fitting.

“An Erebus attack is extremely difficult to detect,” says Min Suk Kang, an assistant professor at NUS School of Computing who specialises in blockchain security. “Even if you can detect it, it’s really hard to track down the perpetrator. So it’s a serious attack.”

Such an attack on Bitcoin, arguably the world’s most popular cryptocurrency, remains — for now — theoretical. It’s something that Kang and his research team began hypothesising and testing on emulators and within a safe, isolated lab setting in 2018. “Our work is to break Bitcoin, with the final goal of making it more secure,” he says.

It may sound counterintuitive at first, but by investigating the vulnerabilities of Bitcoin’s system and its underlying blockchain technology before attackers exploit them, we can come up with solutions to guard against attacks.

Figures from December 2018 reveal that an estimated 32 million people hold Bitcoin wallets, 7.1 million of whom actively use the virtual currency as a form of investment, or to purchase a variety of goods such as Microsoft apps and games, Bjork’s latest album, and sometimes drugs or weapons on the dark web.

While Kang and his team looked specifically at unleashing an Erebus attack on the Bitcoin network, they concluded that the attack could potentially have far more wide-reaching effects, given that more than 40 million people worldwide use some type of cryptocurrency. “An Erebus attack doesn’t just affect Bitcoin, but other cryptocurrencies that work similarly to it, by copying Bitcoin’s source code in their network. Essentially, our attack is effective against at least 34 out of the top 100 cryptocurrencies,” Kang says. “That’s pretty scary.”

Partitioning chaos

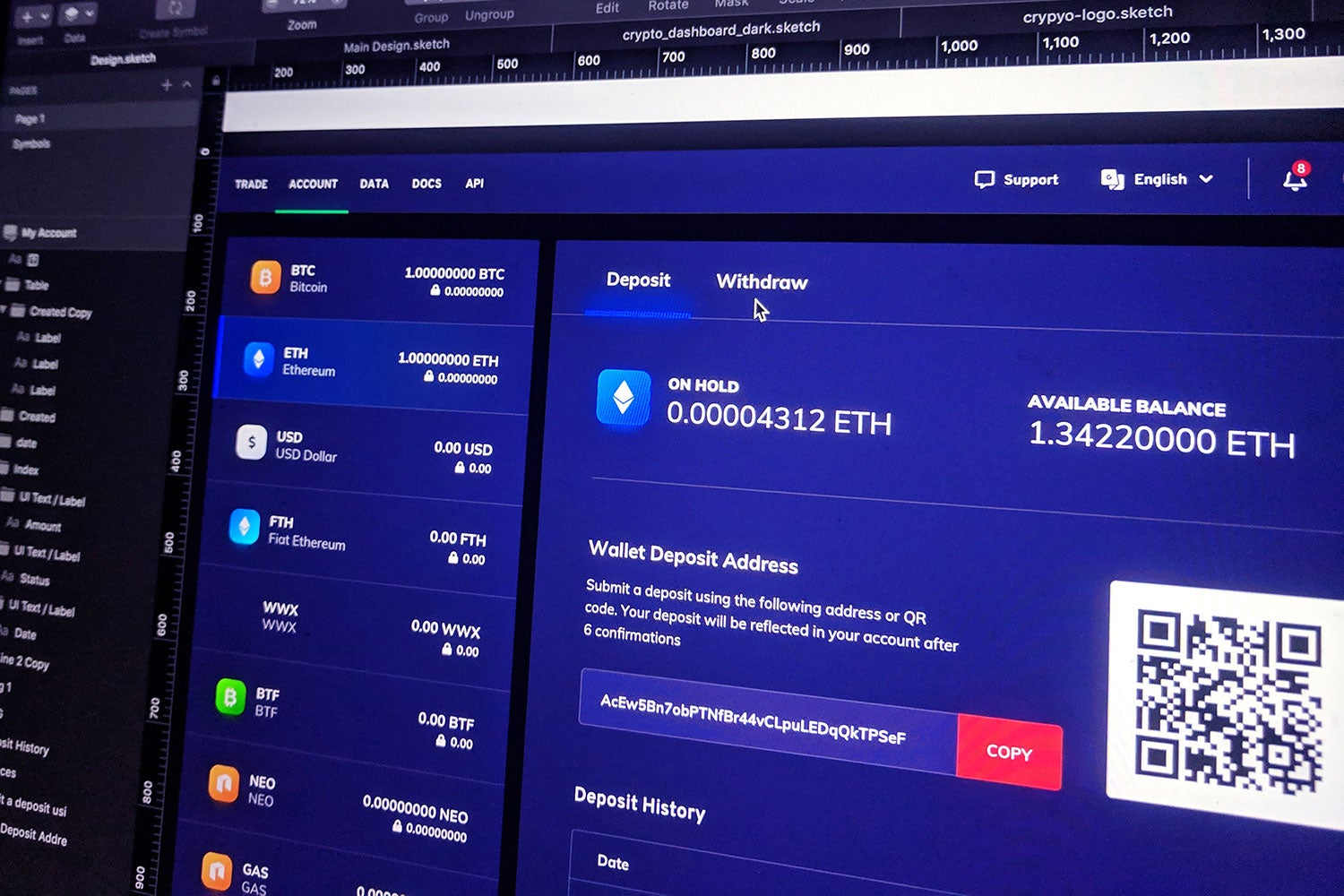

Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies such as Litecoin, Zcash, and Dash are virtual money. Users transfer money between one another using a digital wallet app on a smartphone or computer.

Many cryptocurrencies rely on blockchain technology to work. A blockchain is a list containing information about every single transaction that occurs using the currency. Users, who work from individual computers across a vast peer-to-peer network, independently audit and verify each transaction, or block, before it gets added chronologically to the chain. The resulting list, also called a distributed ledger, is publically available for all to see.

While blockchain works on an underlying principle of transparency and having information on all transactions visible and known to users, Erebus isolates certain users by partitioning the network.

“If Alice is buying something from Bob and paying Bob, then this information should be broadcasted to everyone in the network in a timely manner,” explains Kang. “But if you can partition the network in an arbitrary way, you can block that from happening and you can control the information flow.”

The result: chaos within the system. A victim could be prevented from using her Bitcoin, or have her funds stolen. Fraud could occur in the form of double spending, where a single Bitcoin is spent more than once. The adversary launching the attack could gain majority control of the network’s computing power and thus interfere with how new blocks are added to the chain, in what is called a 51% attack.

“You can even bring down the entire blockchain,” says Kang.

Erebus attacks are particularly dangerous because they do not exploit any specific vulnerabilities in Bitcoin’s core software, which means no quick or simple patches can be used as solutions. Instead, those who control the attack rely on an approach that sets Erebus apart from other types of attacks: by acting as a middle man to subtly influence which peers users connect to within the network. In comparison, traditional attacks forcibly manipulate such re-routing.

“You talk to the victim, gently nudge them, and give them lots of suggestions,” explains Kang. “You’re not manipulating the routing at all, so that’s why an Erebus attack is nearly invisible,” explains Kang.

The goal is to influence the victim “to connect to IP addresses or other computers that are specifically chosen for this purpose,” he says. “As an adversary, you want the victim to talk to specific peers and not others so you can see and control everything. For example, you may want to delay messages between them or just drop the messages altogether.”

Only certain types of attackers have the capacity to influence and partition the Bitcoin network in such a way — namely, large-scale Internet Service Providers (ISPs), especially Tier 1 networks that have the broadest coverage. “The attack works by exploiting the topological advantage of being a large ISP, sitting in the centre of Internet topology,” says Kang. “Thus, nation-state adversaries, who may control large transit ISPs, are able to mount an Erebus attack.”

Foiling Erebus

As dire as an Erebus attack sounds, there are ways to guard against it. “We can’t prevent the attack, but it is possible to make it much harder,” says Kang.

The computer scientist and his team have come up with a promising solution, which involves altering the Bitcoin networking protocol slightly so that the algorithm that chooses which peers a user connects to is aware of the topology ISP network adversaries can adopt. It’s a change that Bitcoin core developers are looking to implement when they next update their network.

Kang and his team are also in discussions with Bitcoin regarding another possible countermeasure, called “peer eviction policy.” It’s a solution that will be more complicated to execute than the first, and involves improving the same algorithm but in a way that provides it with additional information for better decision making. The algorithm, for example, will be able to “see” the messages, or transaction information, a peer is trying to send a user. If the information is outdated, it’s a red flag warning the system that the peer has been compromised by an Erebus attack, says Kang.

He and his team have published a paper describing the attack and the proposed solutions. They will also be presenting their research in May 2020, at the 41st IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, to be held in San Francisco.

Still, Kang says their work must continue. “We have a couple of different countermeasures that are effective, but they are not 100 percent effective,” he says. “Our goal is to propose a new network protocol for blockchain with security principles in mind.”

“Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies deserve a highly secure networking protocol and that’s what my team is trying to achieve now and in the next couple of years.”

Paper:

A Stealthier Partitioning Attack against Bitcoin Peer-to-Peer Network