When you’re ill, seeing the doctor is one thing. Getting your prescription filled is another. If you live in an industrialised country, you probably wouldn’t think twice about the latter — you walk into a pharmacy and there’s the medication you need.

But if you live in the developing world, things aren’t always so easy. In a 2009 study conducted by the World Health Organization (published in the acclaimed Lancet journal), researchers examined the availability of 15 important generic medicines across 36 low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). What they found was discouraging: only 64.2% of such medicines were available when patients tried to obtain them from private healthcare services. And if they went to public sources, the figure dropped to nearly half (38.4%).

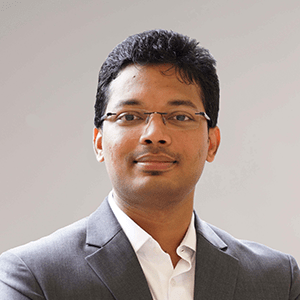

“Universal health coverage is one of the United Nations’ sustainable development goals. It aims for everyone to have access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines,” says Varun Karamshetty, a microeconomist and assistant professor at NUS Computing. Karamshetty uses information systems and operations management to study issues in sustainability and social impact. “To achieve universal health coverage, streamlining medicine supply chains in LMICs is critical,” he says.

In many developing countries, healthcare isn’t subsidised or provided for by the state. Instead, the private sector plays a prominent role, says Karamshetty. “It’s the primary source of essential medicines for many people.”

In these instances, healthcare is essentially a “for-profit business and market economics are assumed to be in place,” he says. Which makes the discrepancy between supply and demand of medicines all the more puzzling. “This mismatch suggests there are deeper factors at play.”

Too little and too much

Karamshetty first became interested in studying the pharmaceutical supply chain of LMICs when he was studying for his PhD at INSEAD in France in 2018. While there, he began working with researchers from the institute’s Humanitarian Research Group, which focused on how to optimise supply chains during humanitarian crises.

Soon, a nonprofit called PharmAccess reached out to the group, seeking advice on how to improve pharmaceutical supply chains in Nairobi.

As Karamshetty and his fellow researchers turned their attention to studying Kenya’s capital in detail, they quickly realised the situation there was interesting. Nairobi’s patients largely relied on private healthcare services, but — as a large study conducted by one of Karamshetty’s collaborators in 2016 revealed — these facilities tended to severely understock essential medicines while overstocking other drugs. For instance, the study found that on average, the facilities surveyed stocked only 28% of drugs on the Kenya Essential Medicines List.

To gain a better understanding of why this was happening, Karamshetty and his fellow researchers decided that they needed to speak with pharmacists on the ground. In 2018, they visited 45 healthcare facilities in low-income areas of Nairobi — clinics, hospitals, health centres, nursing facilities, and maternity homes.

At each of these places, the team interviewed the managers in charge of making inventory decisions at their respective facilities. The researchers quizzed them about the systems they had in place and their inventory control skills; where they got their medicine supplies from; and the constraints they faced in terms of time, budget, and human resources.

The aim of the study was to understand the underlying causes of the mismatch in demand and supply, says Karamshetty, and to suggest possible remedies for the situation.

Borrowing and lending

After analysing the responses collected, the researchers realised something interesting. “When we talk about understocking of medicines, two most commonly cited causes are supply problems and a lack of incentives for inventory optimisation,” says Karamshetty. “But our findings showed these were of little importance in the Nairobi context.”

Instead, the main reason driving the observed mismatch in demand and supply boiled down to something else: when pharmacies had too little or too much of one type of medicine, the costs incurred to them were relatively low.

“They’re not pinching pharmacies as they should have, which is what happens in more developed economies,” says Karamshetty.

“So typically economic theory says that people pay a cost for understocking medicines, in terms of demand lost. And they will soon realise this and update their inventory,” explains Karamshetty. “On the other hand, if they’re consistently overstocking something, they will soon realise that this is tying up their working capital. They will reduce their inventory to improve their cashflow and assortment. This could bring them a little more profit.”

But in Nairobi, there is little incentive to keep inventory supplies balanced because when a pharmacy runs out of something, they simply “run to their neighbour and borrow those medicines and sell them to the customer,” he says. “One store might borrow paracetamol, then give it back the next day or pay money for it or lend the other store something else.”

“So they have this informal arrangement going on,” says Karamshetty. “Pharmacists in Nairobi, especially those that we interviewed, weren’t feeling these costs because even if they were understocked, they could just go and borrow it. And if they were overstocked, they could just lend their inventory to someone, and everything would be fine.”

Discovering this occurrence was “academically surprising because that’s just not how ‘competition’ in developed economies work, he says. “Can you imagine a Guardian store in Clementi running out of something and then going to the Watsons next door to borrow it?”

“So the market forces that are typically assumed to work and foster competition and efficiency and so on, aren’t in play as strongly in developing countries as we would expect in more industrialised countries,” he says.

Understanding this notion is critical for policymakers, Karamshetty and his collaborators concluded in a paper they published earlier this year. “People work in different ways — you can’t just take the economic theory that’s in place in more developed countries and assume that will work in developing countries as well,” says Karamshetty.

“Whatever works works, there’s no right or wrong way,” he says. “As long as patients are not suffering.”

In the case of Nairobi, the apparent poor availability of essential medicines may not be as alarming as the 2016 survey portrayed. The data is misleading if you just analyse it without trying to understand the wider context, says Karamshetty. Which is why he and his collaborators sought to speak in-person to the pharmacists in charge of inventory control at their respective facilities, rather than simply handing out questionnaires for them to fill in.

“We needed to talk to people on the ground to be able to understand these informal relationships,” he says.

Today, Karamshetty continues to study pharmaceutical supply chains in LMICs and hopes that more researchers will pay attention to this space. “There’s a lot of interesting things happening and we are only just beginning to understand the underlying dynamics. That’s just very exciting,” he says. He hopes that the hypotheses proposed in his paper will help spur much-needed further work on private healthcare facilities in LMICs.

“In general, my broader goal is to build a body of knowledge that showcases how policy-makers, industry-players, and NGOs can leverage information systems, analytics and operations management to create social impact,” says Karamshetty. “And hopefully that will advance us towards the sustainable development goals more quickly.”

Paper: Inventory Management Practices in Private Healthcare Facilities in Nairobi County