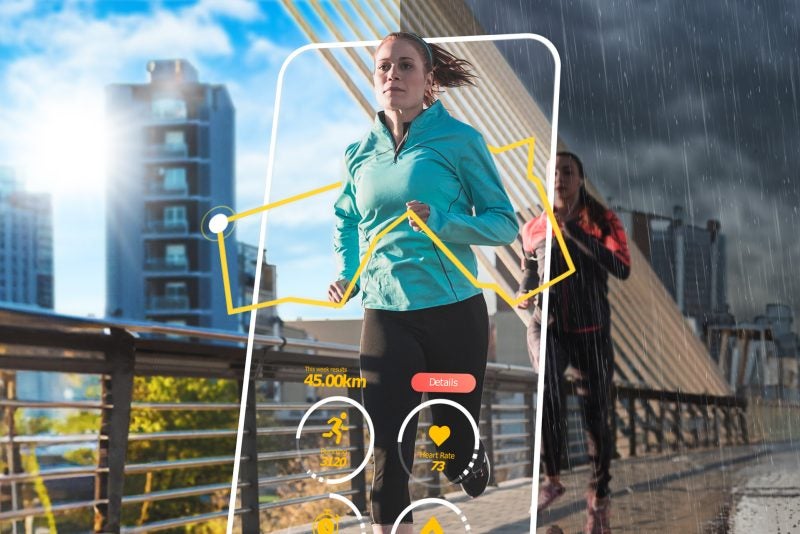

If you like to dabble in exercise — whether as a weekend warrior, Ironman contender, or somewhere in between — you might remember 2015 as being an exciting year. Fitbit announced it was going public, Apple launched its first smartwatch, and the market became filled with a glittering array of swanky yet functional fitness devices you could comfortably wear on your wrist.

Never before had exercising seemed so fun: it was easy-peasy to measure your ‘numbers’ (step count, distance run, calories burnt, average heart rate, sleep quality…you name it), and reviewing them on your fitness tracker, smartwatch, or accompanying phone or desktop app felt like playing a game (all those colourful charts and graphs!).

“Seven to eight years ago, healthcare became a very hot topic,” recalls Teo Hock Hai, the Provost’s Chair Professor of Information Systems at NUS Computing, who specialises in health informatics. “There were many kinds of platforms that emerged to encourage people to exercise.”

But there was one app in particular that caught the attention of Teo and his colleagues. Launched in 2014, China-based FunFitness Pal* allows users to track their walking and running activities, meet fellow exercisers, and compete in numerous challenges.

“The unique part about this platform is that it has a competition element to it, where it urges users to achieve their personal best against one another so there is motivation to exercise,” says Teo.

FunFitness Pal even takes things one step further, by offering exercisers the opportunity to earn points as an incentive. “When you register for the challenges, you ‘pay’ in the form of points, the pooled points form the winnings for each challenge,” explains Teo’s fellow researcher, Sharon Tan, an associate professor at the Department of Information Systems and Analytics (DISA).

“You don’t really see that in other platforms, for example Strava or Runkeeper, which just have leadership boards,” she adds.

The NUS Computing researchers were intrigued. “We thought that was kind of unique and we wanted to find out how such online gamified competitions impacts exercise,” says Tan, who began studying the topic alongside Teo, Goh Khim Yong (associate professor and DISA head) and then-PhD student Yang Yang (now an assistant professor at Warwick University in the U.K.).

Their efforts culminated in an article that was published earlier this year, in the Journal of the Association for Information Systems.

Make it game-like

At its core, gamification is the application of typical gameplay elements — point scoring, competition with others, etc. — to non-game contexts. Businesses, social media platforms, educators, and others employ it as a strategy to build customer loyalty, boost user engagement, and increase motivation, among other benefits. Gamification is everywhere we look these days, from Singapore Airlines’ KrisFlyer to Starbucks’ loyalty programme.

When it comes to exercise, gamification has much to offer. “There’s something about using elements of gaming to sustain interest and pleasure in exercising,” says Goh.

“Some people associate exercise with being a painful sort of activity,” he says. “But by using gamification, there are fun and enjoyable elements, where you have some target to achieve — in the form of either distance or time or being on top of the leaderboard.”

The social aspect gamification brings is an added boon, says Teo. “Some people say when you exercise alone, it can be very boring. But when you exercise with a group of people, you will be better motivated.”

Online gamification also injects an element of competition, which can further create a sense of challenge, excitement, and be an additional motivator, he says.

To study how online gamification impacts exercise behaviour, the researchers analysed data from the FunFitness Pal platform. They categorised users according to whether they were active, moderate, or inactive exercisers, and examined how each of these groups behaved in relation to three factors: performance gap (how an individual performs now versus in the past), performance ranking (an individual’s relative standing on the leaderboard), and rivalry intensity (how he or she makes social comparisons with other competitors on the platform).

Such an approach — of stratifying users based on their exercise frequency — is what distinguishes the study from earlier investigations, says Teo. “One thing we did differently was not treating the population as monolithic. We actually tried to distil the impact of the competition platform on various segment groups, from those who are active, not so active, and moderately active.”

Taking a tailored approach

The researchers’ findings were illuminating. “It’s rare to access this kind of data,” says Goh. “It really enabled us to do a more detailed segment-level analysis.”

The main take-home message from their study, he says, is that there isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach when it comes to motivating people to exercise. “It’s critical to consider individual differences when developing interventions.”

For instance, Goh and his co-authors found that active and moderate exercisers were more motivated when they had information about their performance gap, or in other words how much they’ve improved or deteriorated compared to past performance. But this was opposite for inactive exercisers.

“The more active people seem to have a stronger motivation to benchmark against their own timings, for say a 5-kilometre or 10-kilometre run,” says Teo.

They were also strongly driven by a keen sense of rivalry. “Competing with equally skilled opponents can yield higher levels of competitiveness and desire to win,” write the authors in their paper.

By comparison, those who were just starting out on their exercise journey were less likely “to feel confident in their ability to outperform opponents.” Instead, they appeared more motivated by social comparisons or “driven by external rewards, praises, or comments from friends on the platform,” says Teo.

“Our study suggests that you have different types of users with different activity levels, and they are motivated differently,” explains Tan. That’s a key learning lesson because “a lot of the time what the apps are doing is that they treat everyone the same, when really they should cater to the different user groups.”

Teo elaborates: “I think the key implication is that the platform designer needs to be more careful about selecting the people to join a particular competition…they shouldn’t put people of varying abilities in the same competition.”

For instance, users who are new to exercise or just returning after a long break shouldn’t be placed in a very strong group of competitors, he says. “Because if you keep being the last person in the race, that could be a huge turn off. But gradually as you improve and become more competent in running, you can be placed in a different group.”

The key here, Tan adds, is for the app to evolve with the exerciser as he or she grows over time. “Because you could start off inactive, but become more active subsequently. So as the users change in their activity and behaviour, the app should also change the features that are most salient to that person.” That will go a long way in keeping exercisers motivated, and in ensuring their fancy fitness trackers and smartwatches aren’t just pretty bracelets.

*Name changed to protect privacy, as per the confidentiality agreement