In one scene from the hit TV series Star Trek, Dr Bones McCoy runs to the aid of his fallen crewmate, who lies strewn across a barren, other-worldly landscape. He kneels down, reaches for the small handheld device strapped across his body, and waves it over the injured man. Seconds later, the device beeps and a diagnosis pops up on its tiny screen.

The Tricorder — part scanner, sensor, computer, and analyser — is one of those things you wished existed in the real world. It offers up a non-invasive way for doctors to scan a patient’s vital signs, check their organ function, and instantly detect diseases. Given the simplicity of its “point-and-shoot” function, patients, too, could use it to monitor their health at home.

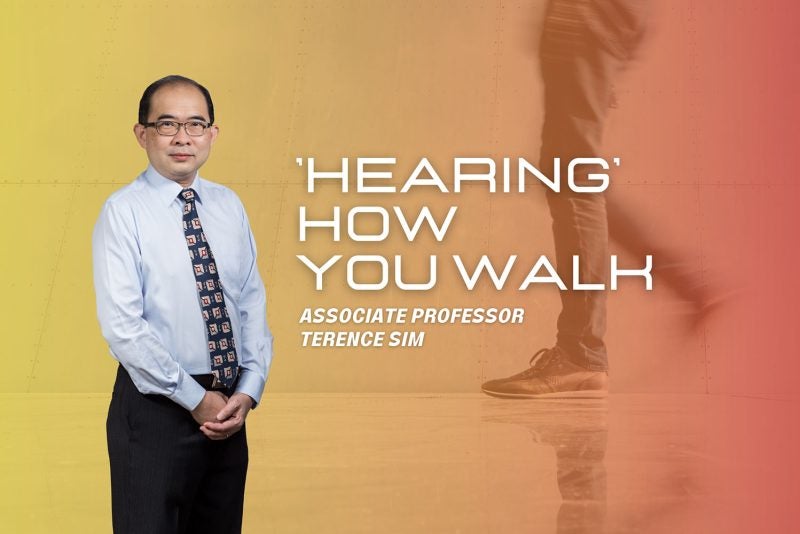

Because of the Tricorder’s remarkable potential as a medical diagnostics tool, innovators have spent the past decade trying to replicate it in real life. NUS Computing’s Terence Sim, a self-confessed Trekkie, is among them.

The time is ripe, says the associate professor, because nearly everyone now owns a smartphone, fitness tracker, or some other type of wearable device. “They are full of sensors and are worn on the body for many hours a day,” says Sim. “Therefore these wearables offer a cheap, unobtrusive way to continuously monitor health and well-being.”

The overall vision, he explains, is to combine the use of multiple wearables to achieve the twin goals of health screening and exercise monitoring. His most recent invention is the EarWalk — a system that utilises earbuds to monitor how people move. It is specifically targeted at those with knee problems, analysing their gait to provide real-time feedback.

Toe in, toe out

Making a link between the ears and the feet isn’t an intuitive one, admits Sim. “I’m actually surprised that it is possible to use earbuds to detect foot posture, given that the ear is located so far from the foot.”

He credits his Masters student, Nan Jiang, for coming up with the idea. Late last year, Jiang was contemplating buying Apple’s newest AirPods. As she looked more deeply into its specs, she discovered something unexpected: the earbuds contained an ‘inertial measurement unit’ — a sensor-filled device typically found in navigation equipment on airplanes and in GPS systems.

“AirPods are for listening to music, why is there a motion sensor in them?” Jiang recalled thinking. Still, she wondered if it might be a useful feature for Sim’s lab to look into.

Around the same time, one of Jiang’s close friends began experiencing problems with her knee, which she soon discovered to be osteoarthritis. The disorder, also called ‘wear-and-tear arthritis,’ occurs when significant stress is placed on the knee due to a person being injured, overweight, or engaging in high-impact activities. Globally speaking, it affects an estimated 16% of those aged 15 and older; in Singapore, the prevalence is roughly one in every 10 adults. “It’s a really prevalent problem not just among elderly people, but also among youngsters,” says Jiang.

“But there’s a really interesting treatment for knee osteoarthritis,” she continues. To reduce stress on the knee, some experts recommend patients walking ‘toe-in, toe out’ — feet facing inwards for one step, and pointing outwards for the next.

But walking in this manner doesn’t come naturally. Physiotherapists often rely on cameras in a clinical setting to capture how a patient walks and provide them with feedback. When Jiang learnt about this, something clicked: what if she and Sim could come up with a cheaper and more practical feedback system using AirPods or other types of earbuds?

Distinguishing Gaits

The researchers — together with their collaborator assistant professor Jun Han, previously at NUS Computing and now at Seoul’s Yonsei University — began building EarWalk in 2021. The aim was to make use of accelerators present in earbuds to detect the force exerted by the ground on the foot as the two come into contact, which would in turn tell whether a person was walking normally, with their toes pointing in, or out.

“We wanted to differentiate between the different walking postures,” explains Sim.

To test whether such a system could work, the researchers recruited eight volunteers and had them walk barefoot on a treadmill. Kitted out with Nokia eSense earbuds, the participants were made to walk for six minutes at a stretch, spending equal time in each of the three different gaits. Each volunteer then repeated this process 10 times.

With the data collected, Sim’s team randomly selected 20 gait cycles to generate a profile for each of the three walking postures. They used these as references to test how well EarWalk worked — to see if the system could correctly predict whether a volunteer was walking normally, with their toe in or out, testing the model on the remaining sample data.

The results obtained were very encouraging: EarWalk was found to be 95% accurate in identifying gait postures. Jiang presented the findings, which are also available to view in this paper, at a recent international workshop held in March. She says “many people were interested in the idea, and wanted to know if we can use it for running and other exercises like weight-training.”

These are applications she and Sim are now looking into, as well as whether they can conduct additional experiments in a more realistic setting outside the lab, where volunteers would be free to walk at any speed they choose and even climb up and down stairs. They also hope to come up with a more generalised model of EarWalk, one that can be applied to any brand of earbuds.

The EarWalk is one in a long line of health monitoring systems using wearable tech that Sim has been experimenting with in recent years. Ultimately, he hopes that earbuds and other wearables will help people better manage their health — by detecting abnormalities early, offering feedback during rehabilitation, and helping exercisers correct their form during workouts.

Sim adds: “Aggregated over many individuals, wearable data can also yield valuable insights into the behaviour and health choices of our population, which can help inform policymakers.”

“Plus wouldn’t it be really cool to finally create a Tricorder in the real world?” he says with a twinkle in his eye.

Paper: EarWalk: towards walking posture identification using earables