Article

- Title: Satellite Mega Constellation for Maritime Navigation: Challenges, Opportunities, and Recommendations

- Author: Taufik Rachmat Nugraha

- Date: 27 May, 2024

- Reading time: 6-8 minutes

Summary

In this article, Taufik presents the risks associated with deploying Low Earth Orbit Satellite Mega Constellation (LEO-Sat MC) in maritime applications and discusses legal challenges and recommendations for regulating LEO-Sat MC.

Satellite Mega Constellation for Maritime Navigation: Challenges, Opportunities, and Recommendations

Taufik Rachmat Nugraha

Research Associate, Centre for International Law–National University of Singapore.

1. Introduction

This article's objective is to understand the current development of the opportunity and challenges of Low Earth Orbit Satellite Mega Constellation (LEO-Sat MC) as one of the primary sources to enhance the navigation capacity of modern vessels and autonomous vessels. LEO-Sat MC offers many advantages such as super low latency only 24-millisecond data transmission and relatively low-cost. However, LEO-Sat MC still lacks regulation from the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), which could result in catastrophes such as collisions and Kessler syndrome if LEO-Sat MC is not immediately regulated.According to the International Association of Marine Aids to Navigation and Lighthouse Authorities (IALA), aids to navigation (ATON) are a “device, system or service external to a vessel to enhance the safety of navigation”. The word "system" refers to the Global Positioning System (GPS) and Automatic Identification System (AIS).

ATON have a crucial role in ensuring the safety of navigation. In the 1983 Tsesis case decision, the vessels were grounded due to the lack of or failure of the Swedish authority to update or maintain ATON and by the decision of the Swedish court that the country was liable since the Swedish authority had not updated the chart and caused the accident. This case is one of the examples of ATON's involvement in the vessel accident. Under the Civil Liability Convention (CLC), there is an exception for ship owners to be liable if the failure comes from the authorities or states.

This case could be repeated for the Low Earth Orbit Satellite Mega Constellation or LEO-Sat MC, recalling until recent days, there is no regulation under international law on satellite deployment procedure and orbital slot regulation on LEO; the ITU only requires coordination to avoid collision. This is different from Geostationary Orbit (GSO), which has been regulated under the ITU.

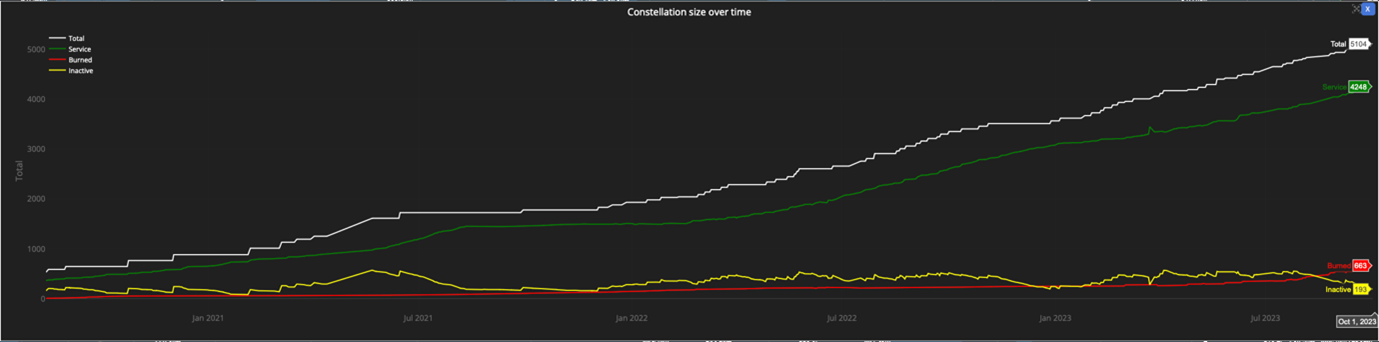

Currently, two of the most significant operators in LEO are Starlink, with 4,265 following the master plan of 42,000 satellites in LEO, and One Web, which has 428 satellites in operation, not to mention other state actors and non-state actors likely have the same intention to deploy thousands of satellites.If this situation occurs, the LEO will be congested with satellites. It can end up catastrophic, such as a collision between a satellite or other space object. Not only that, there is high possibility that humans can no longer launch new satellites, and that does not include the possibility of the radio frequencies, often called Kessler syndrome, leading to future accidents in shipping navigation that uses the LEO-Sat MC service, particularly for Autonomous Vessels.

2. Challenges and Opportunity of LEO-Sat MC for Maritime Application

LEO-Sat MC is still under development, and for the first stage, the LEO-Sat MC is mainly for enhancing internet connectivity for seafarers or passengers. However, in the future, when Autonomous Vessels enter service, LEO-Sat MC will act as a Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS). Furthermore, in the future, Autonomous Vessels will need super low latency uplink and downlink transmission to communicate with their Shore Command Centre (SCC). Moreover, the LEO-Sat MC can cover polar regions and will benefit future polar shipping routes.

This article poses a hypothetical question about LEO-Sat MC: "What if LEO-Sat MC deployment ended up with a satellite collision due to a lack of regulation from the ITU and caused an accident to its user (ship) due to navigational chaos? Who should be responsible for such events?"

That hypothetical question is not without reason: on 25 April 2013, Ecuador's Ecuadorian nanosatellite collided with fragment debris from an old Soviet rocket. Furthermore, in 2021, International Space Station (ISS) astronauts were evacuated several times into emergency pods due to the collision warning resulting from the Anti-Satellite Weapon (ASAT) test conducted by Russia.

Otherwise, referring to the diagram below, those hypothetical questions above are based on the real data that Starlink experienced 200 satellite losses within two months. As we know, the life span of LEO-Sat MC is relatively short compared to GSO, GEO, or MEO sat. Yet, the deployment of thousands of satellites could spike the number of satellite collisions with other satellites and space debris.

The question at hand is a complex one, viewed from two distinct angles. First, the satellite regimes, governed under the 1967 Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies or the OST 1967 and 1972 Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects or 1972 LC, seem to imply that the launching state of the satellite should be liable if the space object physically and directly damages the earth. However, these treaties are silent on indirect damage, such as GPS signal loss leading to a collision, leaving a significant gap in the legal framework.

Secondly, marine oil pollution is subject to a strict liability regime under the 1992 International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage or 1992 CLC. However, it is crucial to note the exceptions, particularly Art 3 of 1992 CLC, which states that “pollution damage was wholly caused by the negligence or other wrongful act of any Government or other authority responsible for the maintenance of lights or other navigational aids in the exercise of that function.”

Article 3 of 1992 CLC may apply with strict conditions and terms if LEO-Sat MC can be treated or categorised as ATON. If not, Art 3 of CLC 1992 cannot be applied.

From a space law perspective, 1972 LC could cover indirect damage, and others could not. If indirect damage caused by a satellite is included under the 1972 LC, the launching state shall be liable for any damage. Under international space law, whether the satellite operator is a private or government entity, the liability issue is attributed to the launching state (the state whose territory is used for launching or the state active in procuring that satellite).

3. Recommendations

Since LEO-Sat MC is still under development from technologies and regulation, there are some recommendations to look forward to in enhancing the safety of LEO-Sat MC for maritime navigation, as follows:Further study to look into the issue of the probability of the system failure caused by the LEO-Sat MC by accident or collision since, from the perspective of space law, there is an unclear meaning of the word “damage”. In this case, indirect damage shall be included in the “damage” definition under OST 1967 and LC 1972. If the fault of LEO-Sat MC causes the vessel collision, the ship owner and the affected state can seek compensation and liability under CLC 1992 and 1972 LC.

Liability should be examined carefully. If the fault is coming from the states or authorities that failed to maintain the safety of the LEO-Sat MC, the ship owner could be exempted from liability if the vessel has an accident and causes damage to the surrounding water, especially for Autonomous Vessels since Autonomous Vessels need more reliable and constant data transfer from ship-to-berth through satellite connection.

It is imperative that we foster further cooperation in the regulation of LEO-Sat MC for the maritime domain such as between ITU, International Maritime Organisation (IMO), International Mobile Satellite Organisation (IMSO) and IALA. This collaboration should extend beyond maritime radio frequency regulation such as Global Maritime Distress and Safety System (GMDSS). It should encompass detailed slot allocation to prevent any space accidents or collisions between satellites in LEO. This collective effort is essential for the safety of LEO-Sat MC and maritime navigation.

ITU, as the regulatory body for satellites, urgently needs to make such regulations and formal guidelines for LEO-Sat MC deployment and allocation. This is to avoid any possibility of catastrophe resulting from the free action that many countries and companies deploy their LEO-Sat.

List of Acronyms:

- LEO: Low Earth Orbit

- MEO: Medium Earth Orbit

- GSO: Geostationary Orbit

- ATON: Aids to Navigation

- AIS: Automatic Identification System

- GPS: Global Positioning System

- GMDSS: Global Maritime Distress and Safety System

- MC: Mega Constellation

- ISS: International Space Station

- ITU: International Telecommunication Union

- IMO: International Maritime Organisation

- IMSO: International Mobile Satellite Organisation

- IALA: International Association of Marine Aids to Navigation and Lighthouse Authorities

- OST 1967: 1967 Outer Space Treaty

- LC 1972: 1972 Liability Convention

- CLC 1992: International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage